Tabletop Roleplaying is something many people know about, but only a few have truly dived into. Today there are thousands of games like Dungeons and Dragons where players take on the roles of heroes and go forth on adventures with the help of dice and stat sheets, all the while being guided by the all-powerful DM, or Dungeon Master. And yet, only recently has this type of game started growing into the mainstream consciousness.

As of my writing this, I have been playing Pathfinder for a little under 3 years. It’s not my first experience with tabletop roleplaying (I played Dark Heresy in University), but it is my deepest one. Admittedly on a relative scale 3 years of gaming is not very long, but my formation has been dense and accelerated. I’ve played in many games and even finished a few of them. But most significantly, I’ve been running a campaign myself (Hell’s Rebels, a Paizo adventure path) since September of 2015.

Even before that campaign, I had wanted to try my hand at DMing. I am, after all, a game designer, and what’s a DM if not the embodiment of a live action game designer? Hell’s Rebels was the first pre-made campaign that really caught my eye, as it featured themes and mechanics that seemed very much in line with my own style. And so, with wide eyes full of excitement I invited a bunch of my friends to join and set forth on my first adventure in DMing.

With modesty, I consider myself to be a fairly decent game designer, though I will wholeheartedly admit I still have a great deal to learn. I am, to be sure, still a junior. But my game has proven to be an intense crash course. My trial by fire was rough to start with, and I made many blunders that looking back on I should have seen coming. I’ve now just concluded the third book (of 6 in the entire adventure) and I’m still learning things with each session. The experience has had its ups and downs, with plenty of fun and fights. But this time as a DM has helped me immensely in learning to become a better designer.

It is for this reason that I’m writing this, a compilation of the key lessons I’ve learned on my adventure. I find that writing gives me a chance to reflect and properly formulate my lessons. At the same time, it is my hope that anyone reading this might learn from my experience. So, without further ado, let’s get right into it.

Tip 1: Know your inner DM

Sun Tzu has some solid wisdom, so I'll paraphrase from him: in war (as in all things), there are three things you need to know to win every time: yourself, your enemy, and the battlefield. My first three tips correspond to these three things.

You as a DM are a crucial part of the game. You need to know what kind of DM you are and by extension what the players will be dealing with. Are you merciful or cruel? Are you by the book or off the cuff? Do you focus on theatrics or mechanics? What are you willing to put up with and what’s a no-go? Take some time to soul search and answer these questions to define your DMing style. Figure out your strengths and weaknesses. It will help you figure out what your campaigns will look like. Telling your players how you're going to run things allows them to figure out if you're running the kind of game they want to play, and what mindset they should be approaching the game with. If the players know their DM, it means they can cooperate with them to make the game go smoothly.

I’ve done an inventory of my own DMing style. My strength is organisation. I'm really good at setting up documents and tools for my players. I like to focus on intrigue and narratives over combat. I like making NPCs that I voice act and give distinctive personalities. I like using music and other tools to set dramatic tones. I don't tend to kill players, but I'll definitely have consequences for poor choices. I prefer interesting but suboptimal characters to optimised stat blocks. I'm generous with items and flexible with game rules of it can make for a more interesting story. I use a lot of DM fudge (DM fudge just means rules improvisation or result altering; I really like the term), but will generally try to stay within a loose script. My theming usually bounces between comical or psychological horror/tragedy. I could go on, but I think I've made my point.

This advice isn’t just applicable in tabletop either. The Art of War has been used in business classes for decades, if not centuries. This quote in particular strikes me as the kind that is truly universal. There are very few times when it is not valuable to know yourself. In knowing your skills, limits, room for growth, and failing points, you can not only better navigate the various challenges, but you can also uncover ways to better yourself as you go. It doesn’t matter if you’re a DM, a game designer, or anything else.

Tip 2: Know your players

Not that your players are enemies (nor should you treat them like ones; I'll get back to that), but they are the ones you're challenging. Having a group of players that doesn't mesh well with you, your campaign, or each other will almost always break a game, or at least make it pretty lame. When you set up a game, make sure the players well be well suited to it. Or if you're making a campaign for an existing group, make the campaign fit them. Don't take on players that won't mesh with your DMing style. Make sure you know the optimal number of players for your game (in most cases it's 4-5, but there are exceptions), and stay within those bounds. Make sure you don't select players that won't get along. Avoid all these mistakes, and it will save you a lot of headaches in the long run.

I made several of these mistakes with my first campaign. I invited people from my various social groups, and it's obvious not all of them get along. I also have 6 players, which means everything takes much longer. I've managed to mitigate these problems with time, but it's obvious that these choices have made for a much tougher campaign for me to run and rougher for the players. By comparison, I play in a small group with two others and we all work well together. Our synergy is incredible, and the game is much smoother as a result.

Considering user-experience is not unique to tabletop RPGs. Video Games and most product-based industries hail the almighty user, and with good reason. As the target audience of what you’re making, it is imperative that what you make is tailored to their needs and/or wants. This is imperative for designers. That said, it is true of any interaction. The more you know about who you’re communicating with, the better you can respond to them to come to a beneficial arrangement. This is fundamental logic in theory, but it is all too often forgotten in practice.

Tip 3: Know your game, and be passionate about it

The DM and the players are important, but equally important is the campaign itself. It is the third leg of the stool; without one, the other two fall apart. You as a DM are the supreme master of the game world, and you should have the knowledge to back that up. It's important that you have a deep understanding of both the mechanics and lore you'll be using. These are your tools, and without them it's the blind leading the blind, and that doesn't end well. Even if you’re really good at improvisation, if you don’t have a solid foundation you risk going all over the place. The moment a player steps off the beaten path, and trust me they will, you're going to have to tell them what they find, or at least provide a good reason for why that doesn't work. It will also help you determine how to best advise your players when it comes to making choices that complement the setting.

Related to this, if you're interested in running a campaign that is in the process of being written/released I also suggest waiting until it is fully released before doing so. This saves you the risk of accidental contradictions. I made the mistake of starting the campaign before all the books came out, and so I lacked knowledge about some world aspects that would have helped greatly. One specific example comes with my friend having picked a character race that played a role later in the campaign (and had a settlement nearby), but because the race and their settlement weren't outlined, I couldn't propose ways in which the player might integrate them into his own story. As a result, his character lacks in the way of tangible motivations that could have really helped with immersion. But it's a lesson I retain for the future.

Now, knowing the setting and mechanics is all fine and good, but that's not enough. You need to be passionate about it. After all if you don't care, why should your players? There are hundreds if not thousands of game systems, worlds, and campaigns out there, and if you're ambitious you can make your own. There's no excuse for you to run something you aren't fascinated by. And if the one you picked has bits you don't like, remember that you're the DM. You can change them. Replace or alter NPCs, places, rules… You are allowed to do all these things and more to make something you're as eager to have your players explore as they should be to explore it.

I specifically picked my campaign because I was very interested in its basic premise and setting. When I started my lore knowledge was okay but as we continued I did a lot of research. Now when it comes to the city of Kintargo and its surrounding areas I could tell you just about anything. I also threw in many new characters and flavour for existing ones to give it more life, and it meant players cared much more about them than they might have otherwise. It was important that the players feel invested in the world, so I made a point to invest in it myself. I think that is my one biggest success with my campaign.

Tip 4: Leave no rules ambiguous

It's a fairly common for rules to be debated during a game. Either someone doesn't like the way a certain thing works, or someone's actively abusing a linguistic loophole, or the rules are ambiguous or contradictory. As the DM it's your job to be the final word on these things. Whether you want to listen to a player's argument and bend the rules or decree that that is not how that thing works no matter how much the player might want to empty the ocean by putting it in their bag of holding, the choice is up to you. But you do need to make sure you set that rule and set it definitely so that players know what goes and what doesn't. Players squabbling over mechanics take precious time away from playing the actual game. Of course some of these only come up circumstantially and can't be predicted, but for those ones just use your absolute authority as DM to sort them out as they appear.

I've seen this quite a few times, both in my game and others, and no example is more prevalent as the alignment system. Would torturing a cultist to get crucial information about an imminent plot cause a good-aligned inquisitor to fall from grace? Is violent murder evil, neutral, or good if the ones getting murdered were tyrants and bigots? What do lawful, neutral, and chaotic even mean? This debate can get quite heated, and since my game in particular was oriented towards CG freedom fighters combating a tyrannical authority, I knew I had to plug that hole before it came up. After all, one man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist, and I didn’t want my group falling into the trap of thinking that any actions would be justified as “good” just because the villains were evil.

In my case, I laid out Good vs Evil as pertaining to the wellbeing of the local citizens, and Lawful vs Chaotic as being a focus on the written law (Lawful), the spirit of the law (Neutral), and the results (Chaotic) when defining Good and Evil. I also decreed that my judgements on any alignment shifts were allowed one appeal, but only one, and that my decisions were final. All things considered it has worked reasonably well. Admittedly my party does have plenty of moments of dubious morality (the quote “does all this blood count as difficult terrain” comes to mind), but I think through the NPCs and the party itself getting more comfortable with the setting, alignment in particular has gone from being a problem to a narrative factor. It was nonetheless a rough patch in my game that I’ll be more careful with in the future.

Tip 5: Set boundaries for your game

Where my last tip was about boundaries in the rules, here I’m referring to boundaries in the sense of scope of the setting. Too often it can be easy to think “I'll just give my players a rich world and let them find their adventure”. It's a nice thought, and if you're really prepared for it a sandbox can work fairly well. But most campaigns have a storyline or plot of some kind, and the moment there's a trail you need to make sure your players stay on it (with reasonable room for deviation, of course). A lot of this is done at the start of the campaign. Players need to know what type of game they're in, both in and out of the meta. Their characters should relate to the story, and the player should be in the right frame of mind. Otherwise you end up with absurdities where characters have no reason to follow your story's rules and suddenly you're left with all your key NPCs murdered by the “heroes” or players cracking jokes and refusing to take your horror scenario seriously. Certainly you don't want to railroad your players entirely, but they should be aware of what are and aren't good ways of approaching your game.

My players generally struggled with their roles in my campaign at first. I didn't have a full picture of the setting (I naively started once the first book of the adventure came out, not knowing what would come further down the line), and so understanding of the plot was somewhat rough. It meant that my players didn't go for the “fight for the good of the city” aspect the game narrative eventually tried to push, instead taking the “fight to kill the bad guy” approach. It meant the party of would be freedom fighters for justice and liberty were more akin to morally dubious assassins. The campaign assumed players would try using nonlethal tactics, but I hadn't given them much of a reason to even consider them.

I managed to pull this back a bit as time went on through NPC interactions and not so subtle hints that they might want to stop murdering everyone and start being a bit more “heroic” in temperament. Some of that did also involve me privately taking players aside to clear it up, which fortunately worked reasonably well. Next time though, I would definitely be very upfront about what your true objective and motivations are. For instance, the next game I'm planning is a horror game. As such, I'll definitely have to be adamant about not having the comical tangents common to the prior campaign.

Tip 6: Have a session zero

So much of what I've noted so far, and a lot of what will come for that matter, can be handled by simply having a session zero. A session zero is essentially a scheduled session in which the players build their characters together. It gives the players a chance to interact and come up with synergies and dynamics together. It's not called a “party” for nothing, after all. Even if they come from different backgrounds, the characters and players should be able to work with each other. It also gives you a chance to observe, clarify, and offer hints and suggestions at how to prepare for your game. Too many DMs will skip this step, and it's a pity. You can avoid so many major early pitfalls with it.

I had a session 0 for my game, but most of it was actually spent explaining basic rules of character creation to my players who didn't know the system well. Some players simply weren't there for it and I helped them with their characters separately. It meant that the rag tag bunch of freedom fighters were very rag tag. Character concepts clashed, and not in the good “this adds flavour to the party dynamic” sort of way. Characters had wildly different motivations that at times conflicted and lead to characters leaving the party to go on their own. A lot of the issues I had to work out over the course of the first dozen sessions or so could have probably been avoided had it been for a session 0.

Tip 7: Keep a rulebook handy

In the event that you don't know your game’s rules and mechanics by heart (and even if you do), it pays immensely to have an easy to pick up reference for yourself and your players. If you're in person, keep at least one copy (but preferably multiple) of the rulebook on hand. If online, keep a tab or window with them at the ready. This little thing can save you a lot of time. Players don't have to ask you for everything, you don't have to remember all those edge cases and special rules, and rule debates can be solved quickly.

That said, sometimes the rules can be a little much, and in those events I wholeheartedly support making your rules up on the fly. Personally, I like to balance both quite precariously. Since my game is conducted online, I always have a link open to the online Pathfinder guide so that I can quickly look up rules and details when I need it. However I keep an unwritten rule in mind: if looking up the rule is taking long enough that the pace starts feeling like it will be broken, then I’ll give up on looking it up and make up something that makes reasonable sense. Usually my biggest hint regarding the pace is that player’s will start talking about subjects outside of what is currently going on in the game. One other thing that can help is to have certain pertinent rule pages bookmarked or open already when they become relevant. I like to keep links to them attached to relevant tokens or notes so that I can quickly access them as needed.

Tip 8: Keep notes for yourself

If the rulebook covers you for mechanics, your notes should cover the roleplay. Even if the campaign comes from a premade book, it's always good write things out yourself. Your notes should be naturally easier for you to read, and you can include details the source might not have. I keep dialogue scripts, scene descriptions, instructions on what songs and actions to do certain moments, and other details in here, and I have to say since I started using them I've found it immensely helpful. It’s very similar to a design document for a game or a screenplay for a film: these will allow you to prepare scenes in advance so that you can play them out faster and easier while in the game.

Needless to say these ones are just for you, so no player peeking. But of course you can always provide a codex of sorts for their benefit that you fill with info as they go. I started making these after a game where I played as the knowledge bot and had trouble remembering all the NPC names. Fortunately once my DM added a journal it made my life (and the DM's) much easier.

Tip 9: Use secret modifiers

Often times, there are situations where the dice just don't do what you want them to do, and it messes up the game. Say you keep getting critical hits on one party member, and end up killing them early on without giving them a chance to fight back. Say the party keeps failing the check to open a door that's necessary to continue to the next area, with no real alternative path. Here's the thing, you're the DM. You hold absolute power, and therefore bend the dice to your whims. Don't show your players your dice, and it you must, wait until after you've decided they have a result you deem acceptable. Consider adding modifiers based on the situation, even if the rules don't strictly call for it. If someone contests you, remind them that you have the right invoke DM fudge (or fiat, or whatever term you want to use for making stuff up; you're the DM after all).

I am a big supporter of DM fudge, in case it wasn't obvious. I use it often. Not so often that I completely take away the chance of the game, but particularly for situations where one result is significantly more interesting than the other. If the players are trying to get past a door and simply can't get a decent role, I decrease the difficulty so that they do. If an enemy can't for the life of them pose any threat to the players because of poor roles, I change them. If a player really should be able to pass a certain check but the mechanical likelihood of it working is minute, I give them a bonus that accounts for their background.

In many tabletop systems fudge is the simplest way to balance a situation. No system is perfect, and DM fudge is what allows the DM to carry out their job of converting the theoretical rules of the game into practical enjoyment for the players. If that means twisting the rules to suit your needs, so be it. In fact this sort of emergent design is perhaps one of the greatest strengths of tabletop RPGs compared to other types of games, because these things can be done both easily and discretely. In truth I don't always tell them that this is what I'm doing, but in many cases they don't need to know.

Tip 10: Give your scenes flavour

This one is perhaps a bit more subjective, since it applies more to narrative focused games, but nonetheless the application of narrative flavour can do wonders for a game's tone and feel. A well placed voice accent, dramatic reveal, or impromptu description of a scene will help to immerse your players in a way that raw dice rolls never will. You don't have to be an actor either; there are loads of ways to do it. Get some background music, use different tokens, make physical letters or objects as handouts, and encourage your players to get certain mechanical boons for roleplaying. Some systems have the last part baked in already.

Personally, I use several of these techniques. Bosses get special boss music, and I try to decorate my scenes when I can. Anytime a critical roll or particularly special event occurs, I try to narrate it (usually to comical effect). I write session summaries that include pertinent gifs and quips. I give every NPC a unique voice and accent. I write scripts for much of my dialogue. The last one is a bit tricky since players rarely follow your dialogue expectations perfectly, but I solve that but keeping it vague and including branching responses. I can tell you from experience that these things make my campaigns so much better. My players have come to know these characters and will even joke about them outside of the game. Some group favorites are Neddus, THE MOST HEROIC, BRAVE, AND LOUD PALADIN IN ALL THE LAND, AND ALSO NOT THE SMARTEST, Setrona, the sassiest and crudest little Irish tavern owner you ever did see, and the stern Octavio, who in Setrona's words “has that polearm o’ his shoved so far up his arse I figure his sharp tongue's just the blade stickin’ out his mouth”. I was pretty proud of myself for that line.

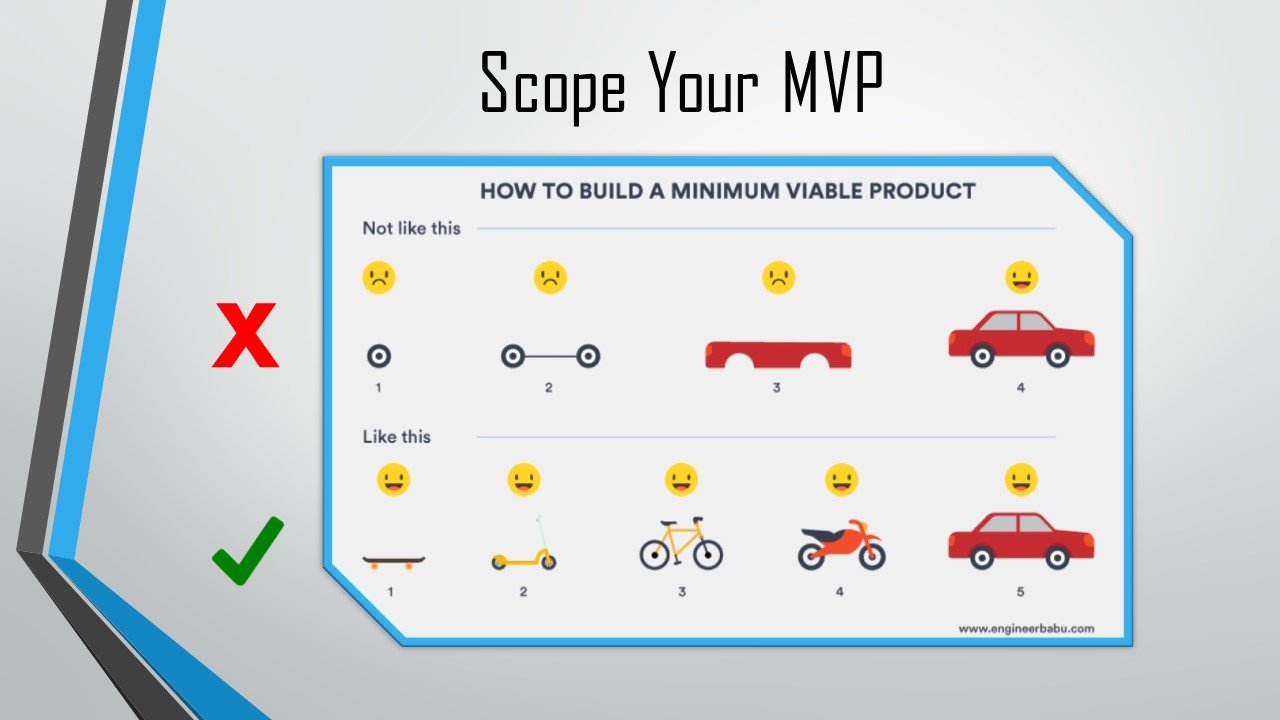

Tip 11: Have a plan, and be prepared for it to derail

One of the big advantages tabletop RPGs have that other games often don't is the flexibility to alter the game on the fly based on how the players interact with the world. A DM is a person, and this means they can be more interactive than any other game system. That said, foolish is the DM that thinks they can improvise the whole thing and actually produce a decent story and progression. I'm not saying it can't be done, but let's be honest: it's never going to be as good as a well-planned scenario.

However, the only thing as certain as the value of a plan of that your players are going to break it. That's just a reality of design: users will always find ways to subvert your expectations. So, don't make a plan with the assumption that your players will follow every little step you give them. They'll jump to conclusions, they'll try things you didn't account for, and they’ll ignore hints. Sometimes it's not even the players, but the dice or some other factor you didn't prepare for. Say your players just really can't hit one particular enemy or don't have a key item they were supposed to get. At one point or another, it will happen, and in those moments, you need to be able to handle it. There are a couple ways to do that, and realistically you should use both of them.

The first is to make sure your plan has contingencies. When I'm writing my session plans, I always include little notes for “what if” situations. I try to include simple details like how the buildings are constructed, basic personality traits for minor NPCs, and the like. I also have standardised values for dice roll difficulties. For example, players must pass 15 on their check to do a basic thing, 20 for a challenging thing, 30 for a very difficult thing (these should be adjusted to match what your players can get on average). Conventions like that are useful for when I quickly need to come up with a check, which leads me to my second solution.

Improvisation skills are your friend. When the plan and backup fail, you need to know how to respond. Knowing your lore is a big part of that (see Tip 3), but some of it is purely on you. I tend to practice a lot on my own scenarios. I'll think about how NPCs would respond to an event and kind of blather it to myself. I’ll consider their comments of shock and confusion, how they'd give advice, and other considerations. I use the same technique on the mechanics side. I think of the feasibility of more outlandish ways to act, and how I'd run them. Some of is intuitive, but thinking on your feet is a skill that can be learned. Take up improv if you can. Or barring that play in games and practice your logic from the other side (how would you deal with your party). And if you don't know whether to let something slide or not, you can always use your dice. Sometimes when a player asks me if something would work and I'm not entirely sure, I'll to a dice or flip a coin to see if I'll allow it. This works pretty decently more often than not.

Tip 12: Check up on your players (and their sheets)

As a DM, checking up on your players is crucial for two reasons. The first is for feedback, the second is to make sure your players are actually up to speed.

There's a general lack of appreciation for feedback in the design world. That's a mistake you as a DM must not make. Talk to your players regularly. Observe them constantly. Find out what they like and don't like about your game. What would they like to see? What are their goals with their character? Do they understand what you're trying to do with the campaign? Get as much feedback as you can, and use it to make your game better. And a quick note: don't just go by the stuff your players tell you either. Actions can tell a great deal more. You need to be observant. Notice when players repeatedly make the same mistakes or regularly avoid or pursue certain aspects of your game. These behaviours can be telltale signs of how to adjust your game to make it more enjoyable.

Then there's the matter of sheet checking. While players should be keeping their sheets up to date, I can tell you from experience they often won't, or they will but not give them to you. While in some cases it's fine to leave it be, in doing so you leave yourself open to some problems. Sad as it is, some players will exploit your lack of oversight to do things which can ultimately be a detriment to the game and their fellow players. Other times they'll make mistakes or forget things. I had one player give themselves a powerful ability they shouldn't have for another four levels because they didn't notice the prerequisite, while another hadn't given himself feats or skill points for the last three levels because he was still learning the system and didn't know what to add on his sheet. It's these kinds of things that can easily be fixed by having your players give you regular sheet updates.

I make sure to demand sheets before any major encounters. Not only does it let me check for these sorts of issues, but it also gives me data on their strengths and weaknesses that I can use to enhance encounters. One rule I plan on using in the future to ensure compliance for games where these details are important is this: “As far as I'm concerned, the last sheet you gave me is the one you have. If you have an item or ability but it's not on that sheet, you don't have it.”

Tip 13: A DM’s words are powerful; use them wisely

There is a reason you are called the Dungeon MASTER. You hold the keys to the game. You know everything there is to know about the game (or have the power to make it up). You are effectively the god of this realm. Don't let that get to your head, but appreciate it. Like they say, with great power comes great responsibility.

Your words can make or break a situation, so you need to act like it. Be prepared to offer advice of a player needs it, and to stay quiet if they need a lesson. The players should care about what you have to say, but at the same time they cannot rely on it alone. Definitely don't tell them what to do (except for very special situations), but instead give them choices (“you could do X or Y”, “do you want to do this thing”, etc.), and occasionally mention likely consequences (“you could do X, but NPC might not be happy”). In drastic situations where a “total party kill” action is about to be undertaken, you also have access to perhaps the most powerful phrase a DM can utter: “Are you sure you want to do that?” Use that one carefully, because it should bring a party to an immediate halt.

It can be pretty intimidating too, I understand, to hold all that influence. There's a trick I use for that. Often times, I'll give NPCs a great deal of wisdom. They'll have plenty of advice on how to deal with various situations. But they will only offer this advice if the players ask for it, or are evidently stuck. As such, I can restrict my advice to “you have people you can ask”. It takes some of the pressure off of me and means I can even toss in the occasional misdirection (after all, an NPC might not know what the DM knows). NPCs are almost universally better guides than the DM, but the DM’s voice is a tool like any other, to be used when you want your players to take what you say as an absolute.

Tip 14: Player agency is an essential thing; handle with caution

By player agency, I mean a player’s ability to control the actions and choices of their character. In any game, agency is critical, but especially so in an RPG. Those characters represent the players. They are yours to manipulate, attack, support, influence… But not control. The moment you take away the player’s control, they aren't playing the game. At best they're listening to your story. There are few things less fun in a tabletop RPG than not being able to do anything in a given situation, be it because you took over or they are in a situation where none of their actions work.

That said, taking away agency from the player isn't completely “verboten”. In fact, it can be an excellent way to instill fear or very threatening situations. Players naturally won't want to lose agency, and when it happens it can be devastating. I think the tensest situation I've ever been in involved one of our party members getting hit with a magic jar spell and getting possessed by a powerful creature. It was scary as hell, but quite fun.

And there's more ways to take advantage of agency as well beyond simply taking it away. Making it work in ways they don't expect (think of how you might adapt something like the Psycho Mantis fight from Metal Gear Solid into tabletop format), mismatching what the player knows and what is happening (a cursed item that does the opposite of what the player thinks it should, for example), giving players different information, messing with basic mechanics… There are some creative things you can do by playing with player agency. To toss an example in, I have one encounter that involves an enemy disguising itself as another player to cause confusion. In Roll20, I do this by making a second character token for that person. The player in question doesn't know which one of the tokens is actually his, and I don't tell the other players either. In fact I don't even tell them the impostor's there. That's for them to notice, hopefully before it's too late.

Tip 15: Give meaning to character deaths

Some systems, campaigns, and even DMs boast about being player killers. I am of the opinion that that is generally dumb, at least in the context of a roleplaying game. Systems that work around the concept of frequent death can work (the game Paranoia uses this to good effect), but what's important to recognise in most RPGs is that players will usually put a fair bit of personal investment in creating and developing their characters. There are exceptions of course, but I'm talking about in general. Death in a system like D&D or Pathfinder doesn't come with an easy respawn until fairly high levels. You need to come up with a new character idea, build that character from the ground up, and even then they might lack the investment of the previous character. It can also be a pretty huge bummer for some people who have long term plans for their character.

Now, having said all that, I'm not against PC deaths outright. What I'm saying is that it's a big deal. It can be an extremely potent narrative tool if you want it to be. But in order for you to make it so, you have to make the death significant, both in cause and effect. There are few things I hate in a game as much as a “save or die”. For those that aren’t familiar, this is the concept of a situation where the player must roll a dice and the life of their character is decided almost entirely on the outcome, with very little the player can do about it. Make sure your players stand a fighting chance, and that if they're dying, it's because of their own poor tactical choices or dangerous risks. You may be the cause of death, but the player must first enable you to do it.

And furthermore, when a PC death does happen, be sure to give them a suitably dramatic send-off. Tip 10 is particularly relevant in these sorts of situations. Let the player have their character go out a blaze of glory. Make it like one of those scenes where a main character gets offed in spectacular fashion. Make a show of it. The more weight you as a DM put on the death, the more importance you are placing on the character's life. It's a good way to further your player's investment in the game universe. The party should feel like they just lost a comrade in arms in a fierce battle, not like Jimmy rolled a 1 so now he has to make a new sheet.

Tip 16: Know what your players are comfortable dealing with

You know what I said about knowing your players? I know it was 14 tips ago, but hopefully the lesson stuck. That lesson goes doubly so for sensitive subjects. Players play games to have fun and enjoy themselves. Things that pull them out of the game by making them uncomfortable just aren't cool. Take note of phobias, touchy subjects, and the like. As abused as they might be in some cases, there's nothing wrong with content warnings either.

Really, this rule just boils down to “don't be an inconsiderate jerk”. If one of your players recently put down their dog and is feeling depressed about it, maybe don't send a pack of zombie dogs after them. If your party isn't into ultra-dark humour, try keeping it to a minimum (or better yet don’t have it at all). Like most things that tread along the edges of depravity, consent, be it explicitly stated or implicit, is important. When it comes to questionable content, some people won't mind if you shove it down their throats, and that's great. But don't do it without getting permission first. Really, not shoving things down people’s throats without their consent is just good practice in general.

Tip 17: Yes it's their story, but you're still the one telling it

At times, the job of a DM might seem selfless, but if that's the case then you probably aren't doing it right. The DM, while they aren't a player character, is still a player in the grand scheme of things. To borrow a term from business, they're a stakeholder, just like the ones “playing” the game. As such, it's critical that the DM also enjoys themselves while running the game.

Well known game writer and DM Matthew Colville once said that the way to determine whether or not a DM has fun depends on whether or not their players have fun. I'd go a bit further than that. Yes, a DM’s enjoyment of the game should be predicated on the enjoyment of their players, but likewise the players’ enjoyment will rely heavily on the enjoyment of the DM. That might sound convoluted so I'll try to simplify: player and DM enjoyment are and should be a symbiotic relationship. One cannot exist without the other, and if either is missing then the game will inevitably fall apart. This is why while many guides about being a good DM talk about improving the experience for players, it's important not to neglect the DM's experience.

This ties in quite heavily with Tip 3. After all, if you aren't passionate about the game, crafting the story within it will seem tedious, and that will rub off on your players. Quite simply put, you won't be a good DM if you aren't enjoying the story you're telling.

Fortunately as of yet I haven't found a situation in my game where I've lost interest in the story. I'd like to think that's a big reason for why my game has continued successfully for as long as it has. However I've certainly seen it with others. There are many times that I've seen a DM lose sight of their campaign's vision, and as a result the game rapidly withered and died. Playing in games where the DM seems to view it as a core just isn't fun, and as a player I wouldn't want to stay in such a game.

Tip 18: Steal good ideas from others

To steal an often misattributed quote, “Good artists copy; great artists steal”. It's an idea that any artist or designer should keep close to heart. After all, it is also said that everything has already been done. So, by extension, anything new is just a really cleverly crafted combination of previously had ideas melded together.

This is particularly true for storytellers. The human experience only has so many divergent paths, including in fantasy. After all even if it is fantasy it should be relatable to your real life human players. There is a great deal of material in the human database, and many great ideas that haven't been fully exploited. Taking these good ideas and making them your own is just being efficient.

That being said, note the wording of my last sentence. “Making them your own” is important. This is the difference between “borrowing” and “stealing” (and by extension the difference between a good artist and a great one, if you follow the opening quote). While taking something cool from somewhere else and transposing it into your adventure is fine, it's even better if you can identify what about that thing made it cool, and rebuild it as a part of your game.

Allow me to offer an example. Though be advised, this is the part where I spoil a rather significant part of the Hell's Rebels adventure path, so if your intention is to play in it I strongly recommend skipping the rest of this section.

Recently, my players attended a masquerade ball being hosted by the villain of the campaign. The players knew this event would be a trap, but didn't know what sort of trap it would be. The trap in question, as laid out in the book, is that at the end of the night the villain locks the doors and has his minions slaughter everyone in attendance while disguised as good-aligned creatures so that he can blame it on the heroes.

However, this plan has some plot holes. If the villain doesn't intend to have anyone survive, why bother with the disguises? If that's a fallback in case anyone survives, then why would he make a long winded speech to the crowd just before the massacre begins calling them “necessary sacrifices”? His attempt at plausible deniability is notably flawed in this regard. Additionally, the villain was supposed to have a bodyguard who would appear only if the party didn't kill them earlier. My party did, so the villain was down a minion, and my group is strong enough that losing that powerful foe would make the fight much too easy.

Fortunately, while going through a forum for DMs of this adventure, I came across a few ideas. For the minion, someone had proposed an alternative that I ultimately used in my game. By this point, the players had thwarted the villain multiple times. The idea was that his bodyguard at the masquerade was his former bodyguard that had failed him in the first book, and was subsequently tortured and upgraded to be threatening to the now much stronger players. Since that one was dead in my game she could not reappear. However, this other DM had pointed out that there was nothing stopping the villain from doing the same thing to any of his other minions that had failed him, and it just so happened there was a foe my players had deceived, rather than fought. For her failure she was turned into the new tortured bodyguard, and served the role very well.

The events leading to the massacre was another proposed alternative I took from that forum. Since the players had done so well to thwart the villain before, it was unlikely that he could kill all 300 people at the masquerade without anyone escaping. Since the villain was in fact a clever strategist, this other DM suggested that the villain conduct a final ceremony that would get interrupted by someone disguised as a player or ally character, so that the lure of the players being the ones responsible seemed more plausible.

I took this idea, but I also fashioned it to suit my group even better. Up until this point, my players had developed a reputation for foiling the villain, but also for using fairly violent means to do so. Many of the villain's subordinates were killed quite brutally. One character in particular, a former slave turned assassin, was known for his violence against those that had wronged him. And so my solution was this: during the final ceremony, certain members of the audience would be brought on stage as winners of the masquerade’s “best mask competition”. Among them was the leader of the noble house most loyal to the villain, who incidentally was the former owner of the slave character, and someone disguised as that same character. During the ceremony, the one disguised as a player leapt at and killed the noble, and was subsequently put down by the villain, but not before claiming his kill in the name of the player characters’ organisation. This served as the panicked pretext under which the massacre began.

The beauty of this solution was twofold. On the one hand, it used the party's own reputation against them. Because they were known for brutally assassinating those loyal to the villain, it seemed perfectly plausible that such an attack would take place, so even if people did escape the massacre (which was likely given the sheer numbers), they might still believe the players to be responsible. On the other hand, because the players were not all together at the time of the ceremony, some of them also believed, briefly at least, that their ally and fellow player had just committed the act, leading to confusion among the party that rendered the whole event that much more chaotic (I made sure with the player beforehand of course that he would be okay with the temporary ire until things were cleared up). The end result was that a scene that otherwise would have made the villain seem foolish now appeared as a much more devious plan that played to the party's faults to give them a greater challenge and a more visceral experience.

Tip 19: Play in games

Technically speaking, there is no rule that a DM has to have ever been a player of the game they’re running. All they really need is a decent understanding of the rules and a campaign to run. That said, it should come as no surprise that playing in games can be immensely useful for any DM. It is by playing in other games that you can see how the game feels from the player’s perspective, but also how other DMs run their games. These offer excellent opportunities to learn by observing others. Countless times I’ve taken good ideas from other DMs I’ve played under, or learned from mistakes they’ve made in their games. By seeing experiences I as a player enjoyed, it gave me a better idea of what to offer my own players. Being on the other side of the DM wall can offer a great deal of perspective, which leads me to my last piece of advice…

Tip 20: Have a life

Tabletop games are immensely fun, and offer a massive array of experiences and opportunities to learn and engage with others. That said, it is only one of many mediums through which you can experience the world. Vast as it might be, it can become possible to get too wrapped up in it, and for it to suffocate your creativity. To refer a little to Tip 18, many of the greatest artists, particularly in the realms of fantasy and science fiction, drew inspiration from other mediums. Isaac Asimov uses his knowledge as a scientist to enhance his stories. Frank Herbert drew heavily from Arabic culture and religion in Dune. George R.R. Martin has an affinity for the history of the European Middle Ages. There’s an entire Wikipedia page covering J. R. R. Tolkien’s influences.

What’s important to recognise is that all of these renowned writers that so often have influenced the domain of tabletop RPGs took inspiration from other sources. To be a good DM, you must be a good storyteller. To be a good storyteller, you must know good stories. And to know good stories, you must look to the world and all it has to offer. Better yet is to live out stories of your own. Go outside, meet different people, and see interesting things. By cultivating experiences first hand, you can draw from them something much more personal than anything you could conceive through pure imagination alone. In fact, I would dare to say that raw imagination is unusable. It can morph and bend things into wonderful shapes, but it needs raw materials to work. These materials come from the outside world.

It would be all too easy for me to shut myself in my room and spend my entire time doing tabletop games. Perhaps if I had, I would have much more experience under my belt than just one game. But I know with absolute certainty that if I were to have sacrificed my life to make and run games, they would be nowhere near as good as what I can produce now. Taking experience from all over the place is what allows me to craft the best work I can, and continuing to have experiences that push my boundaries will only make me a better DM and designer with time. That, quite possibly, is the single most important piece of advice I can offer.

Conclusion

And with that, I’ve reached the end of my lessons so far. As you might have noticed, some are much more practical, others more abstract. But one thing I hope you’ve observed is that all of them, in one way or another, apply not only to tabletop roleplaying games. In truth, any piece of advice I’ve offered here can be just as valid in just about any other domain, be it video games, business, relationships, or anything else. You may need to tweak the terminology a bit of course, but it’s all there. That is something I’ve taken great pleasure in observing in my life: that everything is connected. There are through-lines, universal truths. Systems will often remain consistent from one place to another, and there are a great many transferrable skills that aren’t always known by the same names. To truly recognise this fact, I think, is a key step in being a more complete individual. I won’t be so grandiose as to say it’s the path to enlightenment or anything like that, but I wouldn’t discount the notion.

In conclusion, allow me to offer one final piece of parting wisdom from someone who no doubt has a great deal yet to learn: to be a great DM is to truly understand people. A great DM can touch the hearts and minds of their players and open them to a world of experiences they could only dream of. There is great potential in this role, far more than what might be recognised. I think anyone who has truly been a DM can recognise that. I ask that you hold onto that, and cherish it. Being able to touch others in such a way is an incredible thing, and I really do believe it can bring us together and better us as people. I know that might seem rather lofty for a game, but sometimes the greatest things do come in the strangest of packages. This is, after all, why I chose to pursue the path of a game designer.